Blue Fire and Yellow Brimstone: the world's waning appetite for hellish sulfur

📖 15 min read • Life and death from Satan’s gold

Photo Credit: Candra Firmansyah [CC BY-SA 4.0]

Content notice: child labour, exploited labour / slavery, the Mafia, smog deaths.

It’s just smoke. Floating over the volcano

It’s just smoke. Go on, you know I can’t say no

— “Smoke”, Caroline Polachek, 2023

From hell, life: sulfur eating microbes

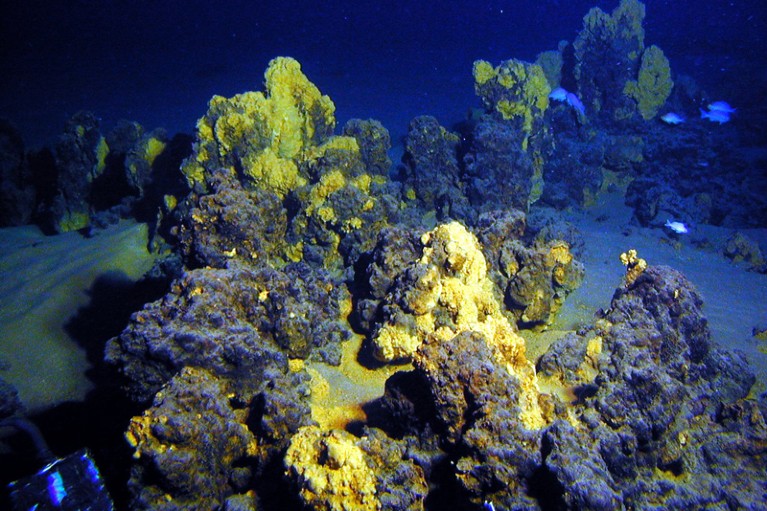

In Earth’s hellish Hadean eon, the embers of ancient modes of life were kindled around geothermal vents, in the deep dark of the sea floor. Billions of years before photosynthesis arose as a way to nurture life from the sun, life found a way to turn the boiling chemical churn of these cauldrons into a stable energy source. The sulfurous nature of these volcano plumes was crucial to the chemotrophy of these Promethean life forms; they could fuel themselves through stripping electrons from this chemical soup.

Archaea at the hydrothermal vents of the Giggenbach underwater volcano 800 km North-Northeast of New Zealand’s North Island. 2005, NOAA Vents Program

4 billion years later, far removed from the sulfur-eating microbes that still cluster around deep-sea vents, humans toil at the base of volcanic craters to harvest the same element for their own purposes.

Mountains of fire: Ijen’s sulfur volcano

In the Indonesian archipelago a mining crew descends before dawn into the bowels of volcano Ijen to start their work. They are often surrounded by the hellfire of the element they are extracting: flames that burn not devilish red but ghostly blue.

Blue fire spewing forth from the sulfur mine around the Ijen volcano complex. Trian Wida Charisma [CC BY-NC 2.0]

These “soldiers of sulfur” are here for emas setan — Satan’s gold. Toxic hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) gases risen hot from the caldera, crashing into the cooler atmospheric air mass. The triggered chemical reaction and phase change is so rapid that sulfur leaves its bonding partners and immediately solidifies. Yellow crystals of the volcano’s breath condense at its base. Most Sulfur mines are now museums for tourists, but were once valuable deposits of the element that fuelled the birth of the British chemical industry finishing the textile trade. Not too long ago, any sulfur deposits were once worth going to war over to guarantee cheap supply.

An infernal gateway: sulfur and the Sicilian Mafia

In 1901 a crew of boys gathers at one of the hundreds of entrances to the sulfur pit mines dotted across the Sicilian province. They are the carusi, the young lads, and their masters are enforcers there to protect the private affairs of the local famiglia, the nascent Sicilian Mafia. The feudal barons had been replaced by territorial landholders just a generation before, when the Sicilian island had been annexed in 1861 to form the unified Italian state.

Six million years prior, the Messinian salinity crisis created the bedrock opportunity for industrial wealth in towns alongside the strait. The evaporating Mediterranean salt water left behind gypsum (CaSO4) crystals that dissolved in the rain to pool in crannies without much oxygen. There, sulfate-reducing bacteria stripped electrons from organic matter and donated them to the sulfur oxidised in sulfate to fuel their own metabolism, leaving behind limestone and native sulfur:

1.5 CaSO4·2H2O(s) + CH3COO-(aq) + H+(aq) → 1.5 CaCO3(s) + 0.5 CO2(g) + 5 H2O(l) + 1.5 S0(s)

‘I carusi’, Onfrio Tomaselli, 1905

Techniques remained primitive. All mining had to be done by pick — explosives risked combustion of the brimstone they were gathering. Working without clothing was common, due to the heat and irritation. Over 400 deaths left records throughout the 1800s, due to flooding, collapse of shoddy mine shafts, or choking on sulfur dioxide fumes. The conditions were so bad that contemporary observers described the organisation to be as cruel as the chattel slavery occurring in the United States.

I am not prepared just now to say to what extent I believe in a physical hell in the next world, but a sulfur mine in Sicily is about the nearest thing to hell that I expect to see in this life.

— The Man Farthest Down, Booker T. Washington, 1911

The conditions of the Sicilian mines are still inscribed in the memories of the Sicilian diaspora to the USA, and a bracing film depicting a child miner’s life in the Floristella mines

The Mafia didn’t instigate these mines, organised sulfur mines had been built in Sicily by the Roman Republic. While sulfur was also widely used by other ancient civilisations (Greek, Egyptian, Chinese), Sicily held unique advantages with its tranquil golden vein of native sulfur. Other ancients had to visit active tectonic sites — like the Greek Island of Milos, or the Aoelian island of Vulcano in the Tyrrhenian sea. China, in contrast, by force of necessity developed complex alchemical ‘roasting’ processes to ‘sweat out’ sulfur from surface pyrites. Liberating the element from its ore and unleashing on the world another innovation of death — gunpowder.

Hellfire: sulfur in gunpowder and Greek fire

Sicilian sulfur was a coveted Medieval commodity: it provided the low temperature ignition of gunpowder, without which there was no thunderous crack of the cannon. A more closely guarded sulfur recipe was for Greek Fire. The Byzantine Empire’s naval flamethrower was devastating — it stuck to everything it was sprayed on but could not be extinguished by water.

“The Roman fleet setting fire to the enemy fleet [led by Thomas the Slav]”. Madrid Skylitzes, manuscript on the Byzantines for the court of Palermo in Sicily, 12th century CE

The mixture for this exact hellflame is lost to history, but early sources for similar concoctions hint at sulfur’s inclusion in this demonic incendiary.

[Automatic fire is composed of equal parts of:] sulfur, rock salt, ashes, thunder stone, and pyrite, and pound fine in black mortar, at midday sun. Also in equal amounts of each ingredient, mix together black mulberry sap and with Zakynthian asphalt, the latter in liquid form and free flowing, resulting in a product that is sooty coloured.

— Kestoi [Fragment D25—Spontaneous Combustion], Sextus Julius Africanus [William Alder’s translation], c. 220 CE

Yellow mammon: sulfur’s economic inversion by the petrodollar

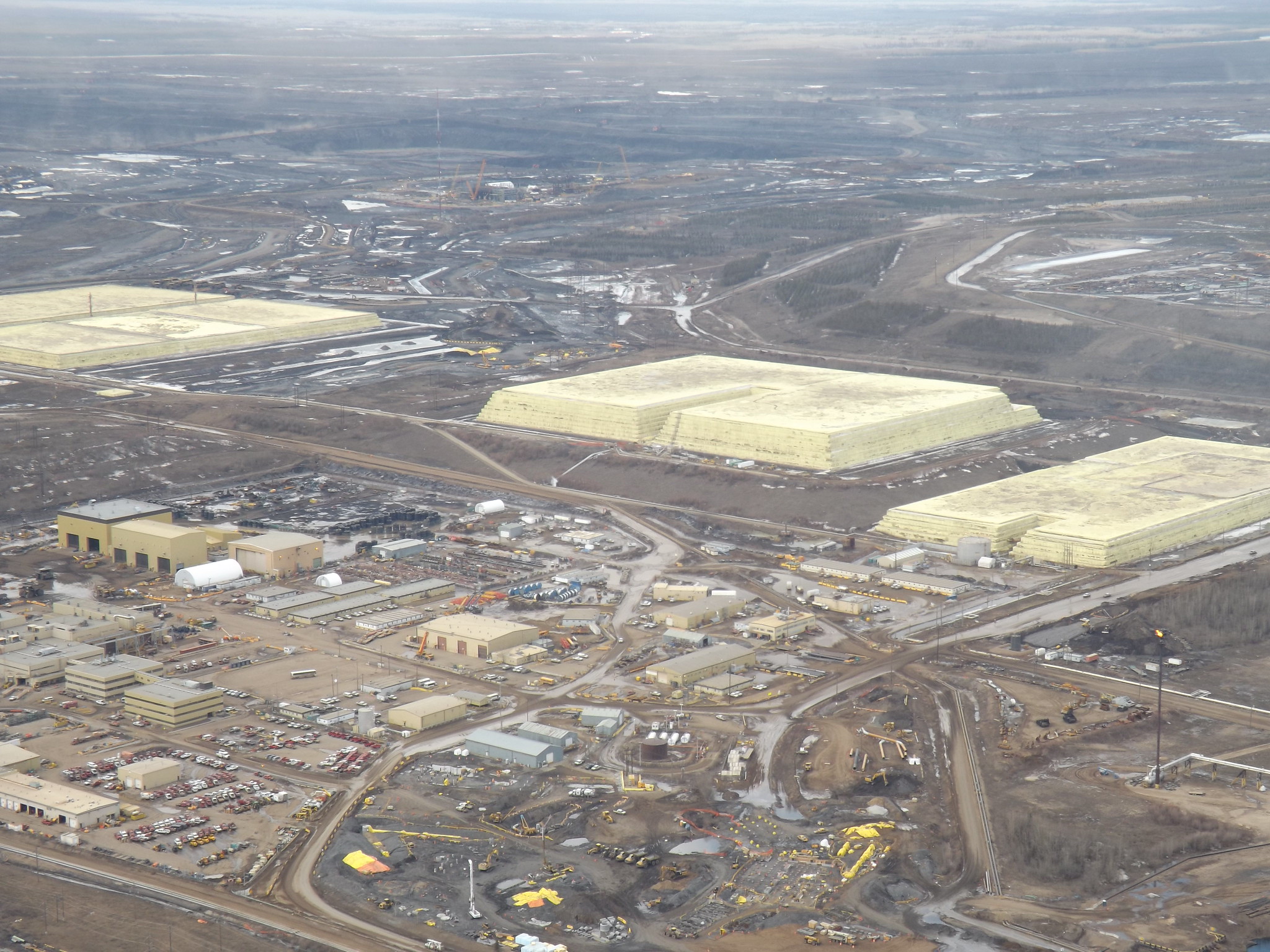

Today, oil refineries pay to have sulfur hauled away. The world can’t consume it faster than stockpiles mount as a waste product of the modern petrochemical industry. Even though sulfuric acid is the most produced chemical by volume, and vulcanisation transformed mechanical goods, nowdays sulfur often commands a negative spot price. From the ravenous fossil fuel gluttony of our combustion-driven world, sulfur falls out for free.

Unwanted mountains of sulfur piling up at the Syncrude Athabasca oil sands in Alberta, Canada. Jason Woodhead [CC BY 2.0]

Sulfur can also be a liability to the petrochemical refining industry. Despite the Orinoco oil belt of Venezuela being the largest in the world, much of the crude is far too ‘sour’ (with sulfur content 6–10x the 0.5% threshold) to be economically viable. Yet this sulfur abundance-turned-burden in our fossil fuels has further unexpected uses.

This economic inversion is what allows researchers to develop ‘no/low cost’ sulfur sponges cooked in –no joke– spent chip shop oil. The sponges sop up chemical waste, forming sulfur-gold bonds. The cleanup applies to both the highest and lowest tech industries in the world: gold can be recovered both from e-waste, and also the poisoned tailings of so-called “artisanal” gold mining. Artisanal gold mining is an industry of desperation; from alluvial deposits or small-scale ore holdings, rudimentary chemistry is used to extract pure gold. Gold readily forms an amalgam with its liquid metal neighbour mercury, which can then be collected by hand. Mercury’s boiling point is low (hence its use in thermometers), so it can be evaporated off from the raw gold on any stovetop. The consequences are harsh: artisanal mining alone releases roughly 40% of global mercury emissions into the atmosphere, the mercury vapours are potent neurotoxins inhaled by the miners, and the waterways are spoiled for all life.

The overabundance of sulfur attests to the sheer scale of petroleum burnt each year. This glut is not a god-given law but an accident of chemistry. If humanity cleaned up its act and decarbonised, sulfur is likely to become a scarce resource again by 2040, with supply stream impacts on our fertiliser and lithium-ion battery production.

Sulfurous sky: SOx and atmospheric pollution

Smog on the front page of The New York Times, photo by Neal Boenzi, November 25, 1966

Sulfur’s calling card is its acrid fumes. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is noxious, notorious for its ‘rotten egg’ smell, and quickly fatal, but the sulfur oxides (SOx) have likely shortened more lifespans. We’ve turbocharged their concentration in the air; through our combustion engine and smelters humanity releases more than twice the suflur dioxide (SO2) emissions than volcanoes. These factories were often near population centres during the Industrial Revolution. Before emissions laws were in place, all it took was a pressure inversion in troposphere to press a smothering blanket of smog down on the cities, as seen in the 1948 Donora death smog, the 1952 Great Smog of London, and the 1966 New York City Smog (pictured above). The response to these hundreds of deaths prompted the legislation of atmospheric protection laws: the 1955 Air Pollution Control Act, the 1956 Clean Air Act, and the 1970 Clean Air Act, respectively.

Such yellow sullen smokes make their own element. They will not rise, but trundle around the globe. Choking the aged and the meek, the weak…

— Fever 103°, Sylvia Plath, 1963

Our industries don’t always out-compete the Earth’s mantle for volume of fumes spewed into the air. Titanic volcanic eruptions can dwarf human activity and shock short-scale climate; in 1816 the eruption of Mount Tambora in Indonesia singlethroatedly caused “the year without summer”. The temperature plunged a couple of degrees, crops failed, and the summer skies in Europe were glum enough to compel Mary Shelley to write Frankenstein.

Such global cooling effects are temporary; aerosolised sulfates increase the albedo of clouds, making them reflect more incoming heat back off earth. Unlike some of the worst “forever chemicals” of our own creation, sulfate emissions are short lived; lasting only weeks before plummeting to the surface as acid rain. Nevertheless, sulfate cooling is detectable: in 2020 the International Maritime Organisation reduced the sulfur limit of shipping’s dirtiest “bunker fuel” from 3.5% to 0.5%. Abrupt sea surface temperature rises and ocean cloud optical changes could be measured. This incidental inverse cloud seeding experiment does not however provide a tidy geoengineering case study to combat global warming: the respiratory and environmental consequences of runaway (SOx) emissions are catastrophic. The processes fuelling our modern life have us in a bargain with Mephistopheles: cleaning up our air exposes the full extent of our millennia-enduring green house gas emissions.

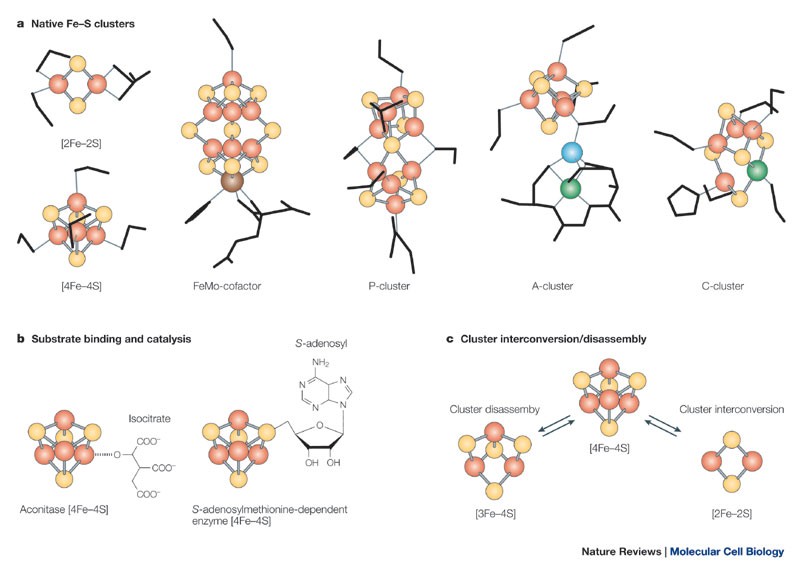

An infernal engine: iron-sulfur clusters and bioelectricity

Sulfur’s changeable electron count makes it useful: it is the non-metal element with the most versatile oxidation state. With a larger outer electron shell than its elemental bunkmate oxygen, sulfur’s third shell provides both readily emptiable or fillable sub-shells (\(3p\)). This gives sulfur bonding flexibility akin to an “expanded octet” that’s facilitated by higher-energy states lying closer to occupied orbitals than in most electron arrangements. By the fourth shell the elements are transitioning into metals, with electrons released into conductive valence band ‘sea’ of electrons characterising metallic bonding. Sulfur, therefore, finds use as a controllable electron exchange junction in redox processes. These junctions are made in the form of iron-sulfur clusters.

Iron-Sulfur clusters that act as waypoints in the electrical process of life, including the reactive ‘crucible’ of nitrogenase. Tracey A. Rouault & Wing-Hang Tong, “Iron-sulphur cluster biogenesis and mitochondrial iron homeostasis”, Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 6, 345–351, 2005.

Electrons —whether generated from cracking an oxygen-phosphorus bond in the ‘battery molecule’ ATP, converted from sunlight by plant photosystems, ingested from Earth’s mineral crust, or swapped during redox in chemotrophy— must be channelled from junction to junction. Life’s electrons don’t typically get to their destination by traveling as free particles; they propagate as waves. This could be through free-space, but the wave is attenuated rapidly over short distances in that medium (around tenths of a nanometer, ~1.7 Å). Even travelling along a ‘non-conductive’ covalent bond is preferable to the vacuum. So, the amino acid linkages in proteins themselves act to wire up the way points (nucleic acids moreso due to delocalised electron sharing between stacked nucleobases).

Along bonds, an electron’s attenuation distance increases, enough to tunnel from bond to bond in a process referred to by physicists as superexchange. Biological electron transfer is therefore a ‘through-bond’ process, and these quantum particles don’t take just one path: the coupling between donor and acceptor waypoints exhibits a wave’s phase, including constructive and destructive interference. The behaviour can’t be explained purely classically, much like the double-slit experiment couldn’t.

The cell’s power is conducted by wavicles tunneling along the molecular bonds connecting life’s electrical circuits, reverberating across pathways and extending into dimensions inaccessible to our prosaic wires of extruded copper. Helping us breathe, helping plants turn photons into fuel. Doing their work to power all life through altering the charge density in the metal-sulfur core of these primordial clusters.

Perhaps these clusters predate—and are a prerequisite for—life itself, states the iron-sulfur world hypothesis. The cell as a waterborne sack to harness electricity. Enzyme cores remodeled from, and still resembling, mineral clusters from the Earth’s crust. Both primates and our aquatic volcano microbial ancestors preserve highly coordinated machinery to build iron-sulfur clusters. That is how crucially guarded nature has kept the production of this molecular crucible.

From the dribs of lava that pierced into the crust, a chemical soup contributed to the origins of us all.

… but torture without end

Still urges, and a fiery deluge, fed

With ever-burning sulfur unconsumed

— Paradise Lost [Book I], John Milton, 1667